When NK Commandos Tried To Assassinate South Korea’s President

This Day in the History of the DPRK: January 21, JUCHE 56 (1968)

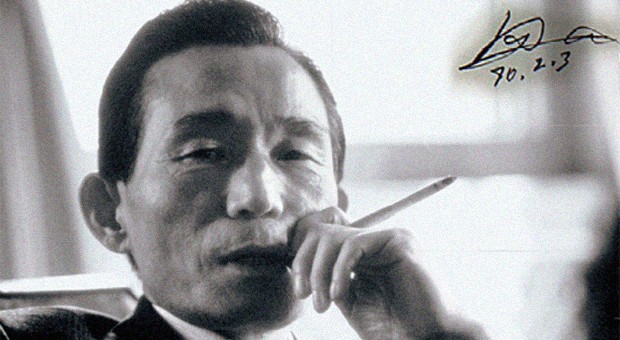

The soldiers, a self-fulfilling prophecy of impending death, advanced unflinchingly with one goal: kill Park Chung-hee, then President of South Korea.

It was dark when it started, just before midnight on January 17, 1968. Thirty-one North Korean soldiers moved stealthily through the DMZ. Reaching a chain-link fence, the men changed into coveralls and army uniforms from the Republic of Korea (ROK). They cut openings in the fence—ever so quietly—and squeezed through onto South Korean territory. Nearby American soldiers, less than a 100 feet away, remained stunningly oblivious. The sun rose on January 18, and the men hid, waiting for the refuge of darkness to move again. They continued on like this, at one point resting less than two miles from a U.S. Army Divisional Headquarters.

And it was all going to plan until the afternoon of January 19, when the infiltrators accidentally came upon four woodcutters. A debate ensued among the North Koreans; an ill-fated decision was made. Rather than kill the South Koreans, ensuring their silence, the commandos lectured them for four hours. A communist revolution, they argued with ideological zest, was coming soon to the south. The civilians were sent on their way with a grim warning: tell the authorities and we’ll kill your families.

The woodcutters went to the police immediately.

The Republic of Korea responded swiftly, deploying troops to seek out and destroy the infiltrators. The North Koreans evaded capture by tapping into radio transmissions and doggedly continuing on to the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential residence. Reaching the mountains outside of Seoul, the city’s bright lights bewildered one of the soldiers, Kim Shin-jo; the capital, he had been led to believe, was shrouded in darkness.

Late on the evening of January 20, clad in the uniforms of the local infantry division, the North Koreans trickled into Seoul in small groups. They met up at Seungga-sa Temple and moved towards the Blue House. Taking advantage of the city’s feverish atmosphere, the group joined in formation and marched as an ROK patrol for the last mile. It was an audacious decision.

The infiltrators marched directly past numerous police and military checkpoints. At some point, however, one South Korean unit second-guessed their complacence and phoned ahead. Less than half a mile from the Blue House, a district police chief’s jeep pulled up, challenging the advancing column for information. Their response was a burst of machine gun fire, killing the policeman and his driver.

Chaos roared. Disparate, roving firefights filled the capital before the North Koreans finally scattered, blasting their way out of the city. The ensuing fighting took the lives of some 36 South Koreans and wounded 64 others. Adding to the terror, a North Korean grenade hit a crowded public bus; another was caught in the crossfire. Twenty-four civilians died.

Members of the doomed assassination squad fled north of Seoul, as authorities, aided by an incensed populace, hunted them mercilessly.

The day after the failed attack one of the fleeing commandos burst into a household and ordered a woman to serve him food. The soldier received a bowl of white rice, ate it, and then promptly killed himself. Another infiltrator, the aforementioned Kim Shin-jo, found himself surrounded that same day. Speaking with a southern accent, one ROK soldier recognized his intonation from his home village and convinced the lone North Korean to surrender peacefully. “I had the desire to live,” Kim Shin-jo recalled of that moment. Following an intense press conference on television, Kim curtly admitted the mission’s purpose: “I came down to cut Park Chung Hee’s throat.” Kim was interrogated for the next year. Eventually, he was pardoned and given ROK citizenship. He later became a Christian pastor.

Of the remaining DPRK soldiers, 27 were killed in numerous firefights in the eight days after the raid. Just two are thought to have made it back across the DMZ, three U.S. soldiers the cost of their escape.

If the Blue House Raid ratcheted up tensions to a level unprecedented since the Korean War, North Korea’s sudden seizure of the USS Pueblo on January 23, and Park Chung-hee’s vehement insistence on direct retaliation, took the peninsula closer to the precipice of oblivion.

It was a dangerous time.

Park Chung-hee’s daughter, Park Geun-hye, is the incoming President of the Republic of Korea. She begins office in February.

For further reading:

- Bolger, Major Daniel P. “Scenes from an Unfinished War: Low-Intensity Conflict in Korea, 1966-1969,” Leavenworth Papers, No. 19 (1991).

- Lewis, Flora. “Seoul Feels a Cold Wind from the North,” The New York Times, February 18, 1968.

- Sarantakes, Nicholas Evan. “The Quiet War: Combat Operations Along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, 1966-1969,” The Journal of Military History (April 2000), 439-458.

No comments:

Post a Comment