North Korean Leader Vows ‘High-Profile’ Retaliation (NYTimes)

By CHOE SANG-HUN

Published: January 27, 2013

SEOUL, South Korea — Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, has ordered his top military and party officials to take “substantial and high-profile important state measures” to retaliate against American-led United Nations sanctions on the country, the North’s official media reported Sunday.

North Korea did not clarify what those measures might be, but it referred to a series of earlier statements in which Mr. Kim’s government has threatened to launch more long-range rockets and conduct a third nuclear test to build an ability to “target” the United States.

Mr. Kim threw his weight behind his government’s escalating standoff with Washington when he called a meeting of top security and foreign affairs officials and gave an instruction in his name. He inherited the posts of supreme party and military leaders from his father, Kim Jong-il, who died in December 2011.

By calling such a meeting and having it reported in state news media, Mr. Kim appeared to be asserting his leadership in what his country called an “all-out action” against the United States, unlike his father, who tended to remain reclusive during similar confrontations.

“At the consultative meeting, Kim Jong-un expressed the firm resolution to take substantial and high-profile important state measures in view of the prevailing situation,” said the North’s Korean Central News Agency, or K.C.N.A. “He advanced specific tasks to the officials concerned.”

The K.C.N.A. dispatch, which was distributed on Sunday, was dated Saturday, indicating that the meeting in Pyongyang, the capital, took place then. That was the same day on which the North’s main party newspaper, Rodong Sinmun, said that the United Nations Security Council’s resolution last Tuesday calling for tightening sanctions against the North left it with “no other option” but a nuclear test.

“A nuclear test is what the people demand,” it said in a commentary.

The resolution was adopted unanimously — with the support of the North’s traditional protector, China — as punishment for its Dec. 12 rocket launching. The Security Council determined that the launching was a cover for testing intercontinental ballistic missile technology and a violation of its earlier resolutions banning North Korea from conducting such tests.

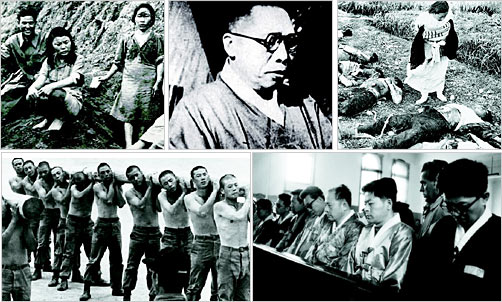

The North rejected the old resolutions, as well as the latest one, insisting that launching rockets to put satellites into orbit was its sovereign right. Its successful rocket launching in December, coming after a failure last April, was the most visible achievement Mr. Kim’s government could present to its people, who have suffered decades of poverty and isolation. In North Korean propaganda, defending the rocket program is likened to protecting national pride and independence — even if the country has to pay a high economic price.

Last Thursday, North Korea said that its drive to rebuild its moribund economy and its rocket program, until now billed as a peaceful space project, would be adjusted and redirected toward efforts to foil hostilities by the United States. On Sunday, it said the Security Council’s action “has thrown a grave obstacle” in the way of its efforts to focus on “economic construction so that the people may not tighten their belts any longer.”

Still, it said it had to “defend its sovereignty by itself” because “different countries concerned” failed to “fairly solve the problem.” In the past few days, North Korea, without citing China by name, expressed bitterness and defiance against its longtime Communist ally for endorsing the American-led Security Council resolution. On Saturday, the Rodong Sinmun reaffirmed its dislike of “sadae,” or toadying big countries, including China.

China provides all of North Korea’s fuel and remains its biggest trading partner, but analysts believe that its influence is limited on the recalcitrant government in Pyongyang. Beijing has been thus far reluctant to use its economic leverage, fearing that it would only drive its neighbor into more provocations, which would be a blow to China’s interest in maintaining stability in the region.

International attention has focused on the Punggye nuclear test site in northeastern North Korea, where the country conducted its two previous underground nuclear tests, in 2006 and 2009. Enough preparations have been made there recently that a third test could happen on short notice from the North Korean leadership, South Korean officials said.

In a report issued Sunday, the Institute for National Security Strategy, a research organization affiliated with South Korea’s main intelligence service, said that North Korea might use provocations this year to tame the incoming government of President-elect Park Geun-hye, who will be sworn in next month.

“It will wait and see until the new government’s North Korea policy shapes up,” it said. “If the policy is not favorable, the North may lash out with provocations.”